Knowledge on Heartworm Disease in Pets

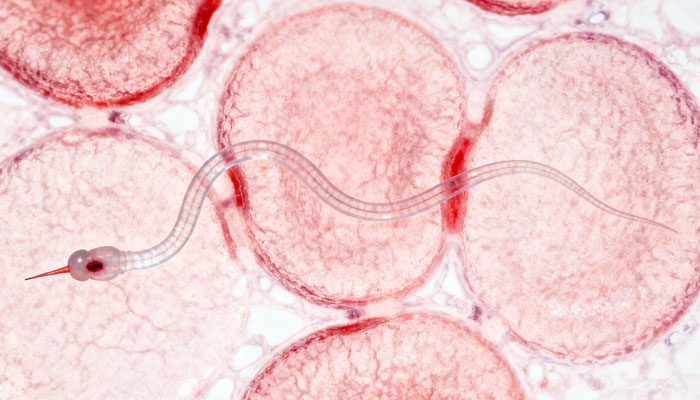

Heartworm is a type of filariform parasite that infests the hearts of pets. The larvae of this parasite typically survive for three years within an animal’s body, while adults live approximately two to three years, averaging 18 to 28 centimeters in length.

When mosquitoes—acting as vectors—bite infected dogs, the larvae enter the mosquito’s body through the infected dog’s blood. After approximately two weeks, the larvae mature into microfilariae within the mosquito. When the mosquito subsequently bites another host, these microfilariae enter the dog’s body to complete their growth cycle. Upon entering an animal, the larvae initially reside in connective tissues. Over the next four months, they gradually migrate to the pulmonary arterial circulation and heart, ultimately causing dysfunction in the cardiopulmonary system.

Heartworm infestation not only damages the heart and lungs but, in severe cases, can cause permanent loss of kidney filtration function. In cats, for example, even an infection with just two heartworms can lead to sudden acute death without warning. Once infected, the worms obstruct blood flow, severely impairing cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic function. While primarily targeting the lungs and pulmonary arteries, these parasites frequently cause ectopic infections in the brain, subcutaneous tissues, and abdominal cavity.

Heartworm infection typically presents no symptoms initially. Larvae mature into adults within six to eight months post-infection. Microfilariae survive approximately one month and can be detected in the host’s peripheral blood as early as 6.5 months after infection.

Clinical Symptoms of Heartworm Infection

Stage I Symptoms: Most animals show no obvious signs during the initial phase of infection.

Stage II Symptoms: Affected dogs exhibit decreased exercise tolerance, lethargy, reduced appetite, and occasional coughing. X-rays may reveal mild to moderate enlargement of the ventricles, pulmonary arteries, and pulmonary lobar arteries. Blood tests may indicate mild anemia.

Stage 3 Symptoms: Affected animals develop cardiogenic cachexia. Right-sided heart failure may cause ascites. As the condition worsens, persistent coughing and dyspnea occur, sometimes leading to hemoptysis. Examination reveals enlargement and deformation of the right atrium and ventricle, along with dilation of pulmonary lobar arterioles and pulmonary arteries. Concurrently, thrombus formation causes pulmonary lobar consolidation, appearing as increased lung density on radiographs. Additionally, anemia is universally present, with packed cell volume (PCV) typically below 20%. Animals at this stage frequently develop portal vein syndrome, clinically detectable through hemoglobinuria and thrombocytopenia.

admin

-

Sale!

Washable Pet Cooling Pad for Cats and Dogs

$10.99Original price was: $10.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

Washable Cat Window Hammock Cooling Bed

$23.99Original price was: $23.99.$22.99Current price is: $22.99. -

Sale!

Tropical Amphibian Rainforest Tank, Lizard Cage

$38.99Original price was: $38.99.$36.99Current price is: $36.99. -

Sale!

Silent 4-in-1 Waterproof Charging Dog Hair Trimmer

$49.88Original price was: $49.88.$47.99Current price is: $47.99.